THE WORLD WITHOUT PHLOGISTON

Sitting on the hill, I watch the sun going down. A pair of wild monkeys, mother and child, is sharing the view. Gentle wind blows, and eventually it shall bring cold distant air to make us leave.

Even the sun goes down. Its energetic light has given the eyes to everyone who was able to 'see'. And yet,the fainter the light becomes, the more brilliant it seems. The faces lit by the glimmering reflections, also look more beautiful as they appear more tired. I wonder why...

'How are you?' 'Fine', of course, being 'fine' is a good thing. but being obliged to be fine isn't the same. Competition among people, the rapid progress of science and technology... Although I'm living in the midst of them, I cannot used to them. All I want to do is to be totally disarmed, become naked from top to toe, let my mind blown in a wind, and watch the sunset. Nothing but to watch the sunset, without any purpose, without threatening or being threatened (sometimes we even threaten ourselves in our effort to obtain freedom and peace), in my thorough innate defenselessness. Kant has once defined 'beauty' as a 'delight apart from any interest'. Possibly we are struggling in vain to be ourselves, misunderstanding all we see...

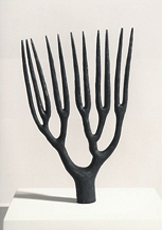

Standing in front of the newest works of Yamamoto, we are forced to scent out a certain puissance rising up from the past. Whoever once has been concerned with art would talk about their 'materiality'. But when we smell out the same scent from these charcoal works as from previous steel and aluminium, we are shocked by Yamamoto's surprising clairvoyance. and the drastic change of taste, which is presumably express in his recent works, does not seem to be caused solely by the change concerning 'materiality'.

Yamamoto's previous works employing steel and aluminium were at his disposition, and so to say remained in his hands. To hear certain sound, discern it from the others, and make it emerge as a figure. Such a constant attitude of Yamamoto has always given his products a low tone, for example in the case of 'LICHEN' as well as in that of 'ARK'. He cut off high-pitched voices and cleared off all the decorations stoically. Each of these works resembled a certain tombstone standing alone somewhere in unknown land.

For all that, as for myself, couldn't help feeling somewhat uncomfortable with these works. What is this uncomfortability? To make a frame, and pour the melted metal into it---that's what Yamamoto has done. Being left to whatever chances, the figures formed by the fall of metal have remained captive in his framework. Some would say; after all, it's nothing but an Artefact, what a humanbeing makes. 'Man cannot live a true life'. By reducing decorations, you inevitably produce another one, and in viewing the pre-human world before you came to be, you cannot but see it with your own human eyes. Yamamoto must have thought of such an anguish, and must have suffer it himself. But you cannot say things like this easily to the others. For this kind of anguish, deeply rooted in human nature, is like a destiny of humanity. That was the reason why, at the time of his last exhibition, I left the place without saying a word to Yamamoto. But now, Yamamoto's charcoal works has surprised me. All the difficulties are overcome. There you can hear a miraclous harmony, you can feel yourself wrapped in a wonderful comfortably. These works are his proper works, in the sense that these are suited appropriately to his original ambition and method.

Noli me tangere. I hesitate, because of a tension included in these tangible objects, that seems to inhibit us from touching them, but unable to resist a kind of gravitation which this tension paradoxically has, I reach out for one of them. Its ashen gray surface, almost lacking its weight, feels sandy and rough as if it is prepared to absorb water, or rather as if it contains invisible water. Touching it, I almost hear the distant sound of the sea. Equipped with innumerable pores, traversed by many crevasses, this surface envelops and transmits multiple waves of the sound, which, emerging at a point of the surface, quietly spread out from within, extend their intensions, and finally reach to the axis of my body so as to rock it gently. Intangible tension touches me, quivering and humming, not as a conflict but as a love. it is a message of the mortal, a splendor of the ephemeral which has held on, survived, and taken form.

Each of the works are named 'PHLOGISTON No....' What is PHLOGISTON? It is an imaginary element, which was supposed in a ancient theory of science to free from every burning body. Certainly the theory has been abolished long since, and we know there's no PHLOGISTON as a physical entity. Nonetheless, now we can conceive of the existence of some other kind of PHLOGISTON.

The fine sculptures, which Yamamoto himself has created with utmost care, he never hesitate to know them into the fire, order to set PHLOGISTON free,so to say, in order to extract something to reveal their and his own essence, anonymous pure essence.

'I'm not afraid of any change the flame shall cause'. Led by the words of Yamamoto, you will be entering unconsciously in the world without PHLOGISTON. If, leaving the place behind, you feel yourself slightly lightened, it must be bscause something essential or excessive has fled from your body.